-

Watches

By Category

Anytime. Anywhere.

By Collection

By Brand

-

Rolex

By Category

By Collection

- Rolex Certified Pre-Owned

- Pre-Owned & Vintage

-

Brands

Watch Brands

Jewelry Brands

-

Jewelry

By Metal

By Gemstone

By Collection

By Brand

-

Engagement

By MetalBy StyleBy Cut/ShapeBuild Your Ring

-

Wedding

By MetalWedding JewelryEditorial

- Sale

-

Sell Your Watch

Sell Your Watch

We will expertly assess your watch and offer you

a competitive and accurate valuation for the

watch you wish to sell to us.Free valuation by our experts

Unrivalled knowledge & expertise

Competitive prices offeredBrands we buy

A. Lange & SohneAudemars PiguetBlancpainBreguetBreitlingCartierIWC SchaffhausenJaeger-LeCoultreLonginesOMEGAPatek PhilippeRolexHeuerTudorVacheron Constantin - Stores

- Shop by Category

-

Watches

- Back

- Shop All Watches

- By Category

- Anytime. Anywhere.

- By Collection

-

By Brand

- Rolex

- Angelus

- Arnold & Son

- Berd Vay'e

- Blancpain

- Bovet

- Breitling

- BVLGARI

- Cartier

- DOXA

- Girard-Perregaux

- Grand Seiko

- Hamilton

- Hublot

- ID Genève

- IWC Schaffhausen

- Jacob & Co

- L’epee 1839

- Longines

- Luminox

- Nivada Grenchen

- OMEGA

- Oris

- Panerai

- QLOCKTWO

- Rado

- Raymond Weil

- Reservoir

- Speake Marin

- TAG Heuer

- Tissot

- Tudor

- Ulysse Nardin

- William Wood Watches

- WOLF

- Zenith

- Rolex

- Rolex Certified Pre-Owned

- Certified Pre-Owned

-

Brands

- Back

- View All Brands

-

A-Z

- Rolex

- Angelus

- Arnold & Son

- Berd Vay'e

- Bijoux Birks

- Blancpain

- Bovet

- Breitling

- BVLGARI

- Carlex

- Cartier

- CHANEL

- Di Modolo

- Dinh Van

- DOXA

- FOPE

- Girard-Perregaux

- Goshwara

- Grand Seiko

- Gucci

- Hamilton

- Hearts on Fire

- Hublot

- ID Genève

- Ippolita

- IWC Schaffhausen

- Jacob & Co

- J Fine

- L’epee 1839

- Longines

- Luminox

- Mappin & Webb

- Marco Bicego

- Massena LAB

- Mayors

- Messika

- Mikimoto

- Nivada Grenchen

- Nouvel Heritage

- OMEGA

- Oris

- Panerai

- Parmigiani Fleurier

- Paul Morelli

- Pasquale Bruni

- Penny Preville

- Persée

- Pomellato

- QLOCKTWO

- Rado

- Raymond Weil

- Reservoir

- Roberto Coin

- Royal Asscher

- Serafino Consoli

- Speake Marin

- Tabayer

- TAG Heuer

- Tissot

- Tudor

- Ulysse Nardin

- Uneek

- William Wood Watches

- WOLF

- Zenith

- Jewelry

- Engagement

- Wedding

- Sale

- Sell Your Watch

- Stores

- My Account

- Wishlist

- Store Finder

- Request an Appointment

- Help & Support

An Introduction To Watch Movements

By Sarah Jayne Potter | 7 minute read

How a watch works all comes down to its movement, also known as the calibre. Think of it as the engine to your timepiece, a complex feat of intricate mechanisms powering both the hands on the dial and all complications. Read on to learn the fundamentals of a watch movement and discover which type is best suited for you.

What is a watch movement?

The main watch movement types, and those we’ll be covering in this guide, consist of:

- Mechanical manual (must be wound by hand)

- Mechanical automatic (powered by the movement of your wrist)

- Quartz (battery powered).

Owing to their impressive complexity and the skill that goes into crafting a movement, watch collectors and enthusiasts pay particular attention to calibres. They can come in a variety of shapes and sizes designed to fit perfectly into the watch case. The thickness of a movement is typically measured in millimetres or ligne. The ligne – equivalent to 2.256mm – is a historic French measure that is still used within the world of haute horology, specifically to measure movements.

Most high-end movements, including mechanical and quartz, are manufactured in Switzerland by watch brands in house or by large-scale movement makers such as ETA, Sellita, and Valjoux. The precise engineering comes from centuries of traditional Swiss watchmaking know-how and we’ll take a closer look at this a little later.

Mechanical watch movements

Up first we have the oldest watch movement – dating back to the 16th century – the manual mechanical. This can be identified as such by the sweeping motion of the second’s hand, if the timepiece features one.

Mechanical movements in general tend to be highly sought-after, as they champion the centuries-old tradition of fine watchmaking. Skilled watchmakers must learn and finesse the craft of painstakingly piecing together many intricate moving parts.

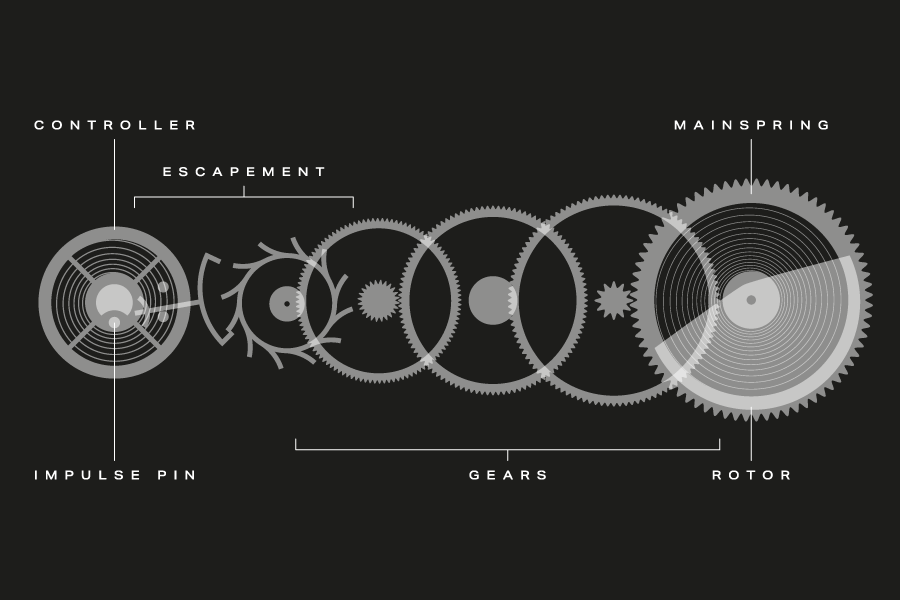

To broadly understand how these parts work together, we must look at the mainspring first. This is a coil of metal that stores energy by winding it tighter and tighter. This then feeds the gear train, which is a system of gears, that in turn powers the escapement – a circular disc with teeth.

Following this, the escapement powers the balance wheel, a weighted wheel that oscillates at a constant rate due to the delicate balance spring. To move the watch hands and keep your timepiece ticking, this requires one oscillation per fraction of a second.

The speed at which a watch ticks is measured in either vibrations per hour (VpH) or hertz (Hz). Today, most high-end mechanical watches beat at a frequency of 28,800 VpH which is 4Hz.

Most watch brands source their mechanical movements from suppliers like ETA in Switzerland. However, some of the higher-end houses with vertically integrated production have the capacity to develop their own movements. These are known as proprietary or ‘in-house’ movements and are highly prized by watch buyers and collectors. Brands such as Rolex, Jaeger-LeCoultre, and Zenith have mastered the art of movement-making, many with patented technology.

There are two distinctions to make when it comes to mechanical movements: manual and automatic. Put simply, manual movements require winding by hand and automatic movements harness kinetic energy from the motion of the wearer’s wrist. Let’s explore the fine details of both.

Manual benefits

- Their tradition and prestige means they are considered highly collectable.

- They can last a lifetime, making them a prime choice as an heirloom timepiece, as there is no need to replace batteries.

- Some luxury timepieces come with the power reserve indicator complication, telling you how long you have before needing to wind again.

Manual upkeep

- Obviously, as they’re not powered by a battery, most will require daily winding. If the watch winds down it won’t keep time as accurately as it should.

- The lubricants can dry up and mechanisms can get dirty. We recommend getting yours serviced every three to five years.

An automatic mechanical watch requires the wearer to move their arm around in order to wind the timepiece. By doing this, the wearer powers a semi-circular metal weight inside, also known as the watch rotor. The watch rotor is able to spin freely at 360 degrees as the wrist moves, and this motion is transferred into energy that winds the mainspring automatically. Because of the need to house a watch rotor, you’ll find that automatic movements are thicker in design than manual ones.

Automatic benefits

- As long as you wear your timepiece often enough, daily winding isn’t necessary.

- You can enjoy the best of both mechanical worlds, as automatic movements can also be wound from the crown.

Automatic upkeep

- Wearing it regularly is advised, as the lack of movement from not wearing it will run the power down.

- As with a manual, the lubricants can dry up and mechanisms can get dirty. A service every three to five years will enable it to continue running smoothly.

Quartz Movements

A timepiece with a quartz movement relies on a battery sending electricity through an integrated circuit to a quartz crystal. These electric charges make the crystal vibrate at a rate of 32,768 pulses per second, and the pulses are then sent through an integrated circuit to the stepping motor. This transforms the electrical impulses into mechanical power.

Each pulse is then sent to the dial train at a rate of one per second and the dial train moves the hands of the watch. It is this process that gives the hands of a quartz watch their distinct individual ticking motion.

A quartz movement was first introduced by Seiko in 1969 with the Astron, and this evolution in technology somewhat derailed the traditional watch industry. In fact, this period of uncertainty was dubbed the Quartz Crisis. During this time, quartz-powered watches made in the USA and Far East (think Timex and Casio) were the height of cool as old-school mechanical watches rapidly fell out of favour.

An estimated 900 traditional Swiss watch brands went bankrupt, and two thirds of the workforce lost their jobs in the watchmaking sector. What was a bleak time for horology soon subsided as the power and heritage of the traditional watchmaking industry enabled it to capture attention and hearts once more.

Benefits

- A great option for new luxury timepiece owners, as they require minimal upkeep.

- These tend to be more reliable and accurate because of their circuit board.

Upkeep

- The battery should last around one to two years. Following this it should be replaced immediately to prevent a battery leak.

Solar Powered

While maybe not as common as mechanical and quartz, solar-powered movements are a viable movement option too, and you may have come across such timepieces from the likes of Tissot. Essentially, they have solar panels hidden under the dial that are used to recharge the battery.

Roger Riehl introduced the first solar-powered wristwatch, the Synchronar, in 1968 and since then brands such as Seiko, Citizen, and Casio have also showcased the technology. Similarly, there are Eco-Drive movements, developed by Japanese watchmaker Citizen during the 1970s. These can generate energy from any light source, whether natural or artificial, and store it in the watch’s power cell.

As the technology has developed, you’ll find that solar-powered watches have come on leaps and bounds, improving in both efficiency and energy storage capacity.

Benefits

- They’re seen as the environmentally friendly choice.

- They are both easy to maintain and reliable owing to their ability to be powered by both sunlight and artificial light.

Upkeep

- Your watch will constantly be charging, so no need to remember to wind it or change its battery.

And a note on Swiss watch movements

It’s no secret that Switzerland is the home to haute horology, and establishes a lofty benchmark for all other luxury watchmakers. It therefore stands to reason that high levels of precision and attention to detail are similarly found in their movements.

A measure of such excellence can be seen in the awarding of a Certified Chronometer status from the Contrôle Officiel Suisse des Chronomètres (COSC) or the Official Swiss Chronometer Testing Institute. Founded in 1973, they certify the accuracy and reliability of Swiss timepieces.

To obtain an exact measurement of the rate of a movement both mechanical and quartz watches are tested over a 15-day period. The test includes checking the regularity of the watch within different temperatures and positions. And of course, high quality components pieced together using the finest watchmaking skills is an integral part of the accreditation requirements too.

Each year, around only 6% of Swiss movements achieve the coveted Certified Chronometer status.